New Deal Infrastructure Projects in Florida

The Genesis of the Car-Dependent Sunshine State

Yamasztuka, December 14th, 2022.

In 1920, the year the first paved highway finished construction connecting Miami with the broader United States, Florida’s population numbered a relatively small 1.4 million people. Nearly a century later in 2022, this number has exploded to 22 million people, over a thousand percent increase. In the same period, Florida would see an economic revolution, building one of the largest and most diverse tourist economies in the United States. Florida’s major population and economic boom in the mid-twentieth century would be directly preceded by one of the largest construction booms in United States history, driven by the road infrastructure projects surrounding the New Deal. Early highways and infrastructure projects in Florida promoted and constructed by New Deal programs directly led to the quick rehabilitation of Florida’s pre-existing economies, the creation of a new middle-class tourist industry, and began the population ascension that would characterize Florida throughout the remainder of the 20th century and beyond.

Before the adoption of the automobile in Florida, the state was extraordinarily difficult to travel around without a train and a large pocketbook. Roads were reported to have been unpaved and pocked with potholes outside of urban areas, often unkept and overrun with vegetation. As stated by the Floridian paper Harper’s Weekly in 1912, the state was “...beyond arduous and impassable sands, behind impenetrable morasses of red gumbo and just around the corner from Stygian cypress swamps and other road unpleasantries.”[1] The population of Florida was largely restricted to the northern border counties, with some major exceptions to the south such as Tampa Bay and Key West. Even rail connections south of Tampa would not appear until the last years of the nineteenth century, with the building of the Florida East Coast Railroad south to the agricultural towns of Miami and Fort Lauderdale.[2] Mobility in this era of Florida was low as many of its residents were far too destitute to afford such a luxury. This is not to mention the Floridian tourist, who in this period was limited to the locations which could be visited by rail and by steamship, largely catering to a class of wealthy individuals who could afford an excursion to the American frontier. This would begin to shift with the rise in popularity of the automobile, and the sudden surge of mobility being available to the middle and working class for the first time.

The adoption of the automobile in Florida would transform and begin to replace the frontier culture which came before. As the price and accessibility of cars began to decrease and become more widespread throughout the 1920’s, many Floridians were suddenly able to become mobile for the first time. This would allow Floridians who resided far outside of the small urban cores to make a day trip into the city, promoting a culture in which urban and rural Florida became more fluid and dependent on one another.[3] Car dependent commodities such as gas stations and department stores began to propagate, promoting the rise of the new American consumerism on the frontier. With the rise of automobile use across the country well in motion, the idea of a paved highway between cities and states began to infest itself in the minds of urban planners. Florida would be first connected by a paved highway to the rest of the United States by the Dixie Highway, which finished construction by 1920. This highway would be the first to connect the American Midwest with the Deep South, from the Canadian city of Montreal running south to Miami.[4] The Dixie Highway and other routes like it would democratize Floridian tourism, allowing middle and working class people to travel south into the state for the first time. New mobile Americans in the middle and working-class found themselves able to travel for the first time, many of which choosing Florida as their destination of choice, and some were here to stay.[5] However, this era of prosperity was not long to last, and would soon be

replaced by one of destitution and depression.

An orange advertisement dating from the 1920’s. It is labelled with the Dixie Highway.[6]

The Great Depression would hit Florida long before any of its contemporaries. In conjunction with the collapse of the real estate boom in the Land Burst of 1926, an invasion of agricultural parasitic insects devastating citrus crops, and the two destructive hurricanes of 1926 and 1928, Florida’s agricultural and tourist economy collapsed in the late 1920’s.[7] South Florida, the impact site of both devastating storms and a land boom collapse, would bear the brunt of this economic disaster. By the time of the Great Depression in the 1930’s, the road infrastructure built in Florida had been partially ruined and was now completely disused by tourists due to the wider depression. This was to the extent that the Dixie Highway in this period was dissolved and absorbed into the new federal US Route system.[8] Florida would be one of the states most in need of support from the federal government, and as luck would have it, President Roosevelt was more than happy to provide. It would be up to the Federal Emergency Relief Administration to rehabilitate many Floridian cities back to a state of operability and sustainability, not to mention tourist friendly. The town of Key West is a perfect case study of the effects of these reforms.

Key West, historically one of if not the most influential and populous Floridian city throughout the period of 19th century American Florida, had fallen on its toughest times in memory. Being an isolated island of little land area, Key West was relatively unaffected by the new economic surge in middle class tourism and the South Florida land boom.[9] Flagler’s railroad remained the only link to the town without embarking on a hundred-mile journey by boat, which many tourists did not venture to do. The island’s residents would be impacted by the depression earlier than almost any in the nation due to the decline of industry on the island, struggling on a subsistence basis of fishing.[10] By the height of the Great Depression in 1934, Key West was in desperate straits. More than eighty percent of their population was on federal relief by 1934, which only hardly kept its citizens alive. The city administration and government, burdened by massive debt, would cease the operation of fire, police, and sanitation, ultimately declare bankruptcy, and cede their powers back to the state of Florida. The Floridian government would request federal assistance for the recovery of Key West, in which Federal Emergency Relief Administration would embark on a journey to bring the town back to its former prevalence.[11]

FERA would propose three solutions to the rehabilitation of Key West, a relief program of two and a half million dollars to prop up its citizenry, the relocation of its three thousand residents onto more sustainable mainland Florida, or riskiest of all, the reformation of the town to function as a new middle-class tourist destination. FERA would choose the latter.[12] In a statement by the head of FERA, Julius Stone, he would state that in Key West, “there would be no blatant race tracks, no blaring night clubs attracting people who cannot appreciate the beauty, quiet and subtle charm of the city. Instead, it will draw the tired businessman, or woman, the convalescent and the artist in the broadest sense of the word.”[13] Forming a group of highly motivated federal workers to drive this reformation, by the fall of 1934, FERA would be on the ground in Key West. The federal government would see Key West as an opportunity to stimulate publicity with the broader American public, both generating positive reception for New Deal programs, as well as promoting the town itself upon completion of their recovery.[14] Broadcast across the nation in newspapers and radio broadcasts, America would witness a new Key West.

CCC members arriving in Key West in 1934. Image from Miami Daily Tribune, August 1934.[15]

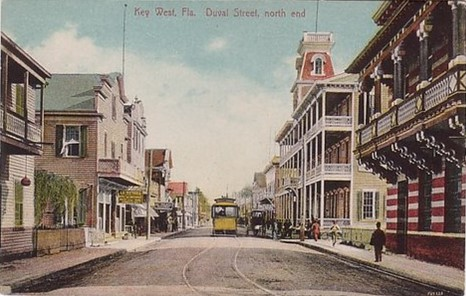

Together with the federal corps from FERA and the combined volunteer labor of the town’s population, Key West would begin its transformation. Undesirable buildings and slums would be destroyed, parks and beach infrastructure created in their place. The brick and wooden homes would be painted with bright colours, with flowering foliage planted wherever possible. Hotels and hostels would be created in all spare rooms available, with rents that were cheap enough to entice the middle-class tourist from a traditional upscale resort. Federal artists employed under New Deal programs would paint murals, create art and pamphlets advertising the new form of the town, and instruct its residents in cultural enriching activities. Amenities lost with the dissolution of the city government were reformed, including the new establishment of a hospital and clinic.[16] By the next year’s tourist season, Key West was poised to open for visitors.

A post card depicting Key West’s Duval Street. Produced in 1935.[17]

1935 would see Key West’s largest influx of tourism in its history, easily double that of previous peak years. Tourists would arrive by train on the Overseas Railway, and most importantly, by car ferry. Frequently running car ferries would allow middle class tourists to drive their automobiles onto the island, enticing those driving south into Florida to take a chance on Key West.[18] In an unfortunate turn of events, however, the Overseas Railway would collapse into the sea during the infamously ferocious 1935 Labor Day Hurricane. However, federal programs under the New Deal saw this collapse as not a setback, but an opportunity. Using the previously built infrastructure that held the railroad, the Overseas Highway would be constructed directly linking Key West by automobile to the Florida mainland. The longest highway bridge ever constructed at that time, the Overseas Highway would be the final nail that would instill Key West as the tourist attraction we know it as today, lifting the island back into prosperity.[19]

The Overseas Highway at its completion in 1938 stretching 100 miles from Miami to Key West.[20]

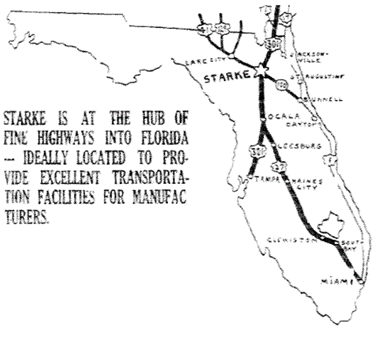

Other portions of Florida would see similar successes under New Deal infrastructure projects. Northern Florida would see significant development during the Great Depression by Civilian Conservation Corps members, constructing bridges, canals, highways, and general-purpose roads throughout the region. The New Dealers that officiated the construction of this new infrastructure, often called “good roads advocates”, would construct many of the semi-modern paved US highways connecting Florida cities allowing for higher speed car travel around the state.[21] An excellent case study to examine regarding this is of Starke, a town in north central Florida. With the construction of these new US Routes, Starke had an unprecedented amount of growth following the 1930s, doubling its population. As reported by the Bradford County Telegraph, Starke was, “Totally unprepared for the tremendous economic changes...Starke was literally bursting at its seams. With Federal aid...every vacant room, garage, and attic was pressed into service...”[22] Starke positioned itself as a business and manufacturing centric city placed perfectly to ship products throughout Florida and into the Deep South, advertising itself as the crossroads of Florida along Highways 301 and 100.[23] These highways also allowed Starke to become a stopover city between northern cities and Miami, with a large hospitality and service industry.[24] Until the rise of the Interstate Highways allowing for toll-free expressway travel throughout the state, much of Northern Florida would see a quick recovery in economic growth due to these new infrastructure projects and incoming tourism.

An advertisement in the Bradford County Telegraph presenting Starke as the crossroads of Florida.

New Deal infrastructure programs would not just change the economies and lives of white Americans living in Floridian cities, but in addition, the native Florida Seminole would also see profound change. The Seminole peoples would arguably be the first in the state to fall into depression, tracing back to as early as the 1910’s. The traditional South Florida swamplands on which the Seminole peoples lived began to be occupied by land speculators following the South Florida land boom, forcing many Seminole from their homes. Consequently, both due to the mass die-off of animal life due to the draining of swamps and the farming of previously forested land, the animal pelt trade on which the Seminoles relied would become insufficient.[25] Many Seminole had to resort to finding employment on the new South Florida agricultural developments in the area to survive. “I lived around here. I grew up here...There was a lot of hunger. If you didn't go looking, or was lazy, if you couldn't help yourself, you would go hungry...”[26] To address this destitution, the New Deal would institute a segregated portion of its Civilian Conservation Corps, entitled the CCC-ID, to assist in the development of infrastructure projects on reservation land in South Florida. The CCC-ID would construct paved roads, modern homes of brick, electric and telephone infrastructure, as well as agricultural projects within the boundaries of federal Seminole reservations.[27] This would allow the tribe for the first time to integrate with the broader Florida, rapidly improving economic conditions for its members, and to come together as a formal tribe as opposed to fragmented villages and groups.[28]

CCC-ID members constructing a bridge over the Myakka River.[29]

Outside of these case studies, the New Deal brought unseen levels of growth to Florida throughout the decade of the 1930’s. The Civilian Conservation Corps would found state and national parks throughout the peninsula, connected by roads accessible by car for the Florida middle-class tourist to enjoy.[30] Old battered Floridian cities such as Pensacola, Jacksonville, and Tampa would see an artistic revival of both murals and writing, transforming their cityscapes and the intellectuals who resided within them.[31] Subsequently, in the latter half of the decade, tourism would see a resurgence higher than ever before. The infrastructure projects that the New Deal created promoted Florida to be a nationwide destination for tourism. In response to this surge of population growth and tourism at new heights, new private housing and infrastructure was built at an unforeseen rate with the new introduction of manmade tourist attractions.[32] While the remainder of the nation would be deep in the dredges of the Great Depression, it would be Florida that would rise out of the ashes before any other region in the United States.

To conclude, Florida’s economic success following the Great Depression period was a direct result in the New Deal programs that modernized its infrastructure. From the creation of programs such as those used to reconstruct Key West, the Civilian Conservation Corps improving road infrastructure across the state and performing essential work for natives, Florida was able to spring out of the Great Depression and into a new age of modern automobile-centric mobility. Through this new infrastructure, the genesis of Floridian middle-class tourism, aerospace, a rapid population boom, and an expansion of wealth would characterize the rest of Florida’s 20th century history.

References

Barnett, William C, “Inventing the Conch Republic: The Creation of Key West as an Escape from Modern America.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 88, no. 2 (2009): 139–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20700280.

Bennett, Evan P. “Highways to Heaven or Roads to Ruin? The Interstate Highway System and the Fate of Starke, Florida.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 78, no. 4 (2000): 451–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30149182.

Florida Back Roads Travel. “History of Key West, Florida. Conchs, Cubans, and Cigars.” Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.florida-backroads-travel.com/history-of-key-west-florida.html. Photo Reference.

Florida State Parks. “Legacy of the CCC at Myakka.” Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.floridastateparks.org/learn/legacy-ccc-myakka. Photo reference.

Gannon, Michael. The New History of Florida. Gainesville, Fla: University Press of Florida, 1996.

Kersey, Harry A. “The Florida Seminoles in the Depression and New Deal, 1933-1942: An Indian Perspective.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 65, no. 2 (1986): 175–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30146740.

Key West Administration. 1934. Key West in Transition: A Guide Book for Visitors. Key West: Published by the Key West administration.

Krause, Robert. “New Deal Public Works in the Florida Panhandle, 1933-1940.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 97, no. 1 (2018): 1–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45210097.

Long, Durward. “Key West and the New Deal, 1934-1936.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 46, no. 3 (1968): 209–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30147763.

Matthews, Eugene. The Story of Starke. Bradford County Telegraph, 1957.

Mays, Dorothy. “Gatorland: Survival of the Fittest among Florida’s Mid-Tier Tourist Attractions.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 87, no. 4 (2009): 509–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20700250.

Miami Daily Tribune. “CCC Boys – 197 Strong – Here to ‘Clean Up the Town.’” August 20. 1934. Photo Reference.

Mormino, Gary. “Twentieth-Century Florida: A Bibliographic Essay.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 95, no. 3 (2017): 292–324. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44955689.

Mormino, Gary. Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams: A Social History of Modern Florida (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2005). ISBN: 9780813033082

Nelson, David. “Rejecting Paradise: Tourism, Conservation, and the Birth of the Modern Florida Cracker in the 1930s.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 96, no. 3 (2018): 328–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44955759.

Parman, Donald L. “The Indian and the Civilian Conservation Corps.” Pacific Historical Review 40, no. 1 (1971): 39–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/3637828.

Preston, H. L. (1991). Dirt Roads to Dixie: Accessibility and Modernization in the South, 1885-1935 (1st ed). University of Tennessee Press.

Rauchway, Eric. “Why The New Deal Matters.” Living New Deal (blog), August 1, 2021. https://livingnewdeal.org/why-the-new-deal-matters/. Photo Reference.

Whitney, Justin. “Florida Expressways and the Public Works Career of Congressman William C. Cramer.” USF Tampa Graduate Theses and Dissertations, November 8, 2008. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/563.

Footnotes

[1] Preston, Dirt Roads to Dixie, 116. Quoting Elbert Henderson, “Winter Tours in Summer Climes,” Harper’s Weekly, 6 Jan 1912, 12-13.

[2] Mormino, Gary. Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams, 25-26.

[3] Gannon, Michael. The New History of Florida, 430.

[4] Mormino, Gary. Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams, 78-82.

[5] Mormino, Gary. “Twentieth-Century Florida: A Bibliographic Essay,” 295-299.

[6] Mormino, Gary. Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams, Photo Gallery in between pages 78 and 79. Photo Reference.

[7] Gannon, Michael. The New History of Florida, 304-306.

[8] Whitney, Justin. “Florida Expressways”, 9-15.

[9] Mormino, Gary. “Twentieth-Century Florida: A Bibliographic Essay”, 301-304.

[10] Barnett, William C, “Inventing the Conch Republic”, 160-162.

[11] Key West Administration. 1934. Key West in Transition, 42-47.

[12] Long, Durward. “Key West and the New Deal”, 212-213.

[13] Julius F. Stone, Jr. to David Sholtz. July 3, 1934, reprinted in Key West in Transition, 62.

[14] Long, Durward. “Key West and the New Deal”, 216.

[15] Miami Daily Tribune. “CCC Boys – 197 Strong – Here to ‘Clean Up the Town.’” August 20. 1934. Photo Reference.

[16] Key West Administration. 1934. Key West in Transition, 71-73.

[17] Florida Back Roads Travel. “History of Key West, Florida” Photo Reference.

[18] Barnett, William C, “Inventing the Conch Republic”, 166-167.

[19] Mormino, Gary. “Twentieth-Century Florida: A Bibliographic Essay.” 302-304.

[20] Rauchway, Eric. “Why The New Deal Matters.” Photo Reference.

[21] Krause, Robert. “New Deal Public Works in the Florida Panhandle”, 29-31.

[22] Matthews, Eugene. The Story of Starke, 5.

[23] Bennett, Evan P. “Highways to Heaven or Roads to Ruin?”, 460.

[24] Bennett, Evan P. “Highways to Heaven or Roads to Ruin?”, 456.

[25] Kersey, Harry A. “The Florida Seminoles in the Depression and New Deal”, 178-182.

[26] Interview with Susie Billie by Jeanette Cypress, May 6, 1984, SEM 187A, UFHA, reprinted in “The Florida Seminoles in the Depression and New Deal”

[27] Parman, Donald L. “The Indian and the Civilian Conservation Corps.”, 142-144.

[28] Kersey, Harry A. “The Florida Seminoles in the Depression and New Deal”, 182-190.

[29] Florida State Parks. “Legacy of the CCC at Myakka.” Photo Reference.

[30] Preston, H. L. Dirt Roads to Dixie, 159.

[31] Gannon, Michael. The New History of Florida, 321.

[32] Mormino, Gary. “Twentieth-Century Florida: A Bibliographic Essay”, 304-307.